Most packaging issues don’t come from bad intentions.

They come from small decisions made too late.

In real projects, quality control often seems complete.

Samples are approved. Inspections are planned.

Yet problems still show up—

after production starts, or even after shipment.

By the time packaging issues become visible,

schedules, costs, and options are usually already compromised.

That’s because packaging quality control is often treated as a final check, not a working system.

In this guide, we share how packaging quality control actually works in real manufacturing projects—

and how it helps reduce risk, avoid rework, and prevent delays before they scale.

Quick Takeaways (What You Should Know in 60 Seconds)

- Not just final inspection — packaging quality control is a decision system.

- Most packaging issues appear after sample approval, not before.

- Different packaging types require different QC priorities.

- Sampling and AQL help manage risk, but they don’t guarantee perfection.

- Our role is to help clients spot risks early and make better production decisions.

What Packaging Quality Control Means in Day-to-Day Production

How we define packaging quality control internally

From a factory perspective, packaging quality control is not about catching defects at the end.

Internally, we see QC as a way to reduce repeatable risk—issues that can happen again if the setup does not change.

That means focusing less on inspection results

and more on whether materials, tolerances, and processes are stable.

If the process is unpredictable, passing inspection once does not remove the risk.

What we focus on first when a new project starts

Quality control starts before production.

At the project stage, the key question is not “what to check,”

but what actually matters.

We focus early on:

- Which specifications affect fit or protection

- Which materials are sensitive to variation

- Which structural points carry stress or alignment risk

- Where small deviations could trigger rework or delays

Setting these priorities early determines

where sampling helps,

where monitoring matters,

and where inspection effort is effective.

Most QC problems are not caused by weak inspection.

They are caused by unclear priorities set too late.

Once production is running, those decisions are expensive to reverse.

Why Packaging Quality Control Matters More Than It Seems

How small packaging issues turn into rework or delays

In real manufacturing projects, packaging issues rarely fail in obvious ways.

They usually start small.

A slight dimensional deviation.

A material reacting differently under load.

A process step that works in testing but drifts in volume production.

On their own, these issues may seem manageable.

As production continues, they compound.

What begins as a minor packaging issue can quickly lead to rework, line adjustments, or temporary stops.

At that point, quality becomes a scheduling problem.

Why problems often show up after sample approval

Sample approval is an important milestone, but it is not a guarantee.

Samples are produced under controlled conditions—slowly, with close supervision and limited variation.

Production runs faster, involves more operators, and allows far less room for correction.

Materials behave differently when machines run continuously.

Setups change.

Human variation increases.

This is why many packaging quality issues surface only after sample approval.

Approval confirms feasibility, not production stability.

What usually costs more: stopping early or fixing late

Stopping early feels disruptive.

Fixing late is usually worse.

Late-stage fixes often involve materials already purchased,

production capacity already scheduled,

and delivery timelines already committed.

At that point, options are limited and costs spread quickly.

What could have been adjusted early becomes difficult to reverse.

Early quality control decisions preserve flexibility.

Late decisions remove it.

Most packaging quality issues become expensive not because they are severe,

but because they are discovered too late.

Quality control matters because it changes when decisions are made—not just what is inspected.

How We Approach Packaging Quality Control Across Different Packaging Types

Primary packaging: where compliance leaves no room for correction

Primary packaging is closest to the product, which means mistakes are rarely recoverable.

Quality control at this level focuses on material compliance, sealing performance, and dimensional accuracy.

If the specification or material choice is wrong, the issue usually affects the entire batch.

Because late adjustments are not realistic, QC for primary packaging emphasizes early validation and stable process control—rather than relying on final inspection as a safety net.

Secondary packaging: where consistency protects your brand

Secondary packaging is where quality becomes visible.

In practice, consistency is controlled through a small number of critical points:

- Color: approved printed samples are retained as golden references; Pantone (spot) colors are monitored by density and, when required, LAB values

- Structure: die-lines and fold geometry are fixed; any mold replacement requires renewed first-article and fit confirmation

- Process: key finishing steps such as lamination and gluing are run within defined parameter ranges

- Assembly: glue points and alignment are checked during line setup, not left to final inspection

When these controls are in place, variation is contained.

When they are not, packaging may remain functional—but brand perception degrades quietly across batches.

Tertiary packaging: where transport stress reveals weak points

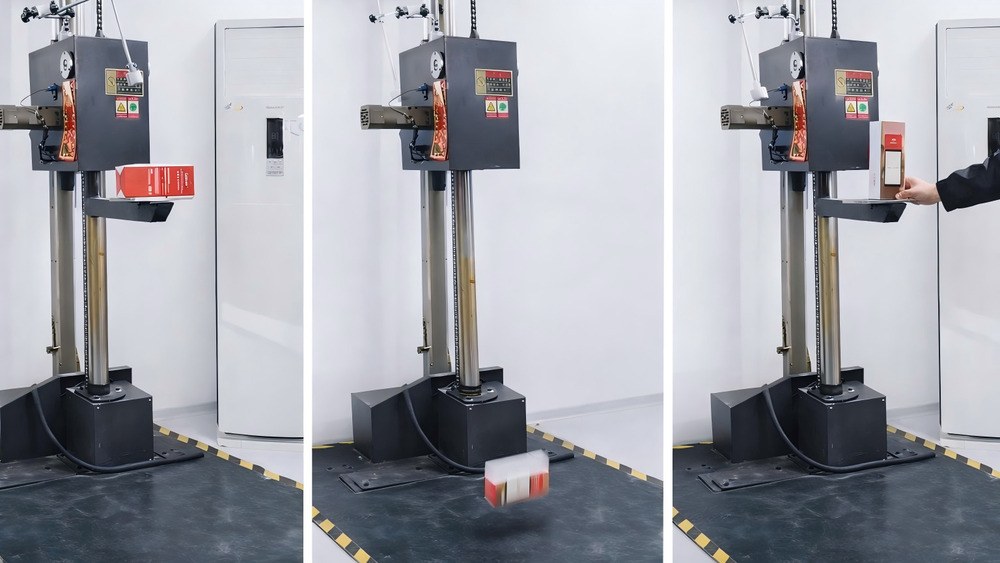

Tertiary packaging is tested in transit, not on the table. We use stress-based validation—including high-humidity testing—to ensure your goods survive extreme maritime routes without structural failure.

Quality control here relies on stress-based validation—such as drop, compression, vibration, and environmental cycling—typically conducted during sampling or pilot stages.

Without this testing, structural weaknesses often surface only after shipment begins, when correction is costly and options are limited.

Different packaging types fail in different ways.

Quality control works only when it reflects real usage conditions—not when the same checklist is applied everywhere.

Our Packaging Quality Control Process (With Real Decision Points)

Before production: what we make sure is locked

Before mass production, quality control is fundamentally about eliminating uncertainty.

At this stage, we make sure all critical elements are clearly locked:

specifications that affect assembly or protection, approved materials, structural geometry, and process boundaries—such as whether paper selection conflicts with coating or finishing methods.

We also strongly recommend providing the actual product for validation.

This allows us to run drop tests from individual units to full cartons, verifying that the product remains functional and undamaged throughout real transport conditions.

All foreseeable details need to be anticipated and controlled.

If an issue cannot be clearly defined or validated before production, it will almost always become harder—not easier—once volume and speed increase.

During production: what we monitor and why

During production, quality control shifts from defining rules to observing real performance.

The focus is not on checking everything,

but on monitoring the points most likely to drift—color consistency against approved samples, material correctness, critical dimensions, and process stability.

This includes first-article confirmation during operations such as die-cutting,

as well as in-process checks across each key manufacturing step.

Small fluctuations are unavoidable in real production.

What matters is whether they remain within controlled limits.

When deviation trends in the wrong direction,

early adjustment prevents minor drift from developing into systematic defects.

Final inspection: what it helps confirm — and what it doesn’t

Final inspection has value, but its role is limited.

It helps confirm that finished packaging meets agreed specifications

and that no obvious issues were missed earlier.

However, final inspection cannot fix unstable processes

or compensate for poor decisions or oversights made during production.

When quality control relies too heavily on final inspection,

it often leads to sorting shipments, restricted use, or complete rejection—forcing rework, rescheduling, and delayed delivery at significant cost.

When we recommend stopping, reworking, or adjusting a run

Stopping or reworking a production run is never taken lightly.

We recommend it only when continuing would clearly amplify risk—

for example, when variation exceeds control limits or when the root cause is not yet understood.

In some cases, controlled adjustments are enough.

In others, stopping early prevents far greater losses later.

These decisions are based not only on pass-or-fail results,

but on whether the process can realistically return to a stable state.

Quality control works only when it supports better decisions at every stage.

When it is reduced to inspection alone, packaging quickly becomes unpredictable.

Prevention and control always cost less than rework or remake—and a systematic QC process is one of the clearest signs of a mature packaging manufacturer.

Common Checks and Tests We Use to Catch Issues Early

Dimensions and tolerances

Dimensional issues rarely fail in obvious ways.

More often, small deviations build up quietly—until assembly becomes difficult, stacking turns unstable, or protection no longer works as intended.

We don’t measure everything.

We focus on dimensions that actually affect fit, alignment, and protection.

When tolerances are defined around function instead of drawings alone,

minor drift can be spotted early—before it turns into rework or delayed shipments.

Materials and print consistency

Material and print issues rarely appear all at once.

Paper behavior, coatings, and print appearance tend to drift gradually across runs.

Each batch may seem acceptable—until variation becomes visible.

We compare materials and print output against approved references,

not just against the previous batch.

Catching drift early prevents small differences from compounding into noticeable defects.

Labels, barcodes, and markings

Labels, barcodes, and markings are often treated as low risk—

until something goes wrong in real use.

Problems rarely come from how a label looks on the table.

They come from how it behaves on the line, in the warehouse, or at the customer’s dock.

Misplaced labels, incorrect content, or incomplete printing can quietly pass inspection,

only to cause scanning failures, compliance issues, or forced relabeling after shipment.

When that happens, the cost is not just reprinting.

It is delayed delivery, manual sorting, and problems found far too late.

Drop, compression, and sealing tests

Some weaknesses only appear under stress.

Drop, compression, and sealing tests simulate what packaging actually goes through—

handling, stacking, and transport.

These tests don’t aim to prove that packaging passes.

They aim to show where it fails.

When failure happens early—during sampling or pilot runs—

adjustments are still possible without disrupting production or delivery.

Most quality issues are easy to detect—

they are just easy to miss at the wrong time.

Targeted checks and early tests move discovery forward,

while decisions are still flexible.

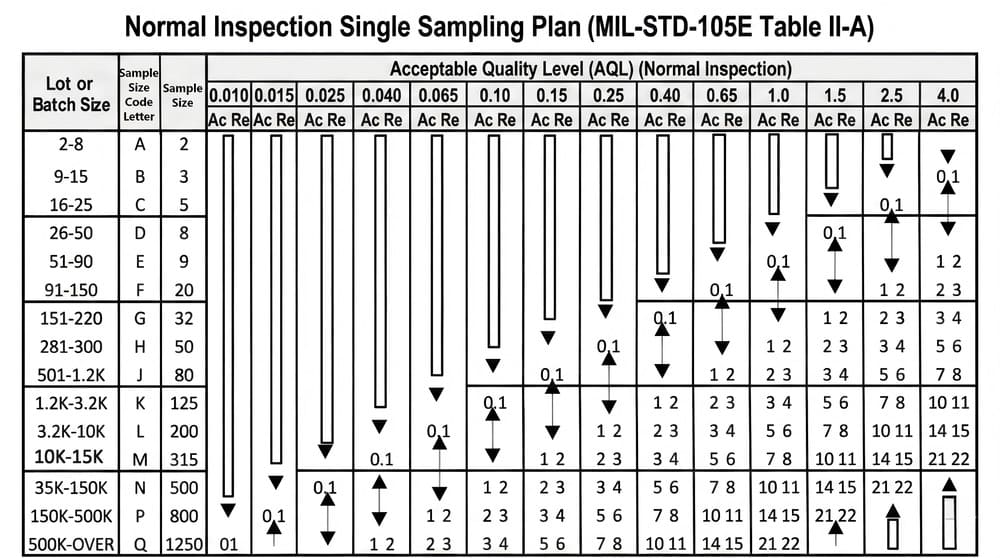

How We Use AQL and Sampling Without Overpromising

AQL as a Common Language Across the Production Process

At Klong Packaging, AQL is not treated as a final checkpoint.

It is used as a consistent reference from raw materials through to finished packaging.

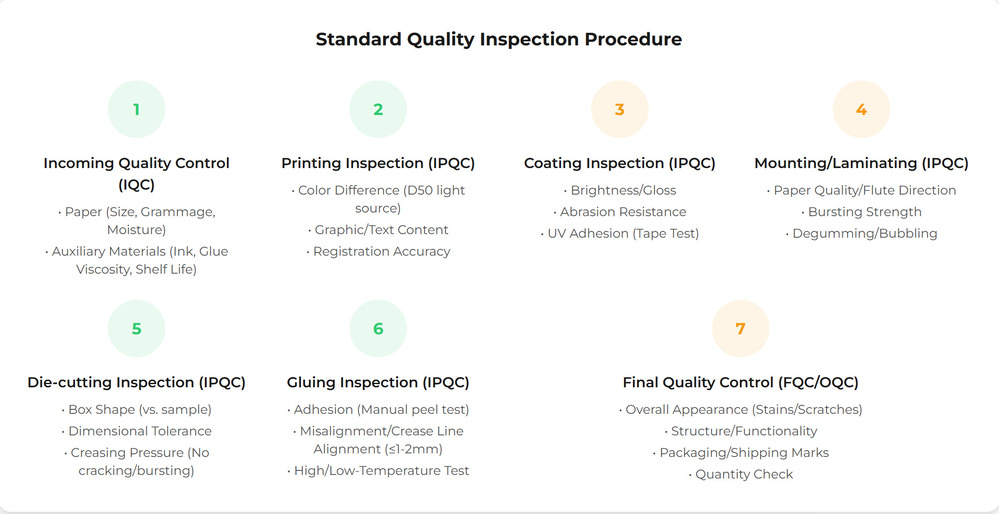

We apply sampling based on ANSI/ASQ Z1.4 and ISO 2859-1 at multiple stages:

Incoming Quality Control (IQC)

Before production begins, raw materials such as paper stock, inks, and adhesives are checked using AQL sampling.

If materials do not meet the agreed standard, they do not enter production.

In-Process Quality Control (IPQC)

During printing, die-cutting, and other key processes, patrol inspections are carried out using AQL tables.

This helps detect early signs of process drift before issues scale into larger defects.

Final Quality Assurance (FQA)

Before shipment, AQL sampling provides a final view of overall batch stability.

Across all stages, AQL functions as a shared language—not to guarantee perfection, but to consistently assess whether the process is under control.

Misunderstanding AQL as a promise of zero defects is one of the most common—and costly—mistakes we see in packaging projects.

Why We Combine 100% Inspection with AQL 1.0

AQL is effective for monitoring system stability, but in many packaging projects, individual defects still matter.

That is why our final stage combines two complementary approaches:

100% Full Inspection

Every unit is visually inspected before packing.

This step removes obvious defects such as scratches, glue overflow, or visible color mismatch.

It is a screening process focused on individual units.

AQL 1.0 Final Audit

After packing, we conduct a random audit using AQL 1.0.

This audit is not meant to re-inspect every unit, but to verify that the inspection process itself remains reliable.

Using AQL 1.0—stricter than the commonly used AQL 2.5—helps ensure that quality does not rely solely on human screening.

Making AQL stricter does not automatically make quality better—beyond a point, it only shifts risk and cost without improving process stability.

How This Layered Approach Reduces Risk

Many packaging issues occur when quality checks are concentrated only at the end.

By applying AQL at the material stage and during production, and combining it with 100% inspection before shipment, risk is addressed at multiple points rather than discovered too late.

This layered approach does not eliminate defects entirely, but it significantly reduces the chance of unexpected issues after goods leave the factory.

When products are released for shipment, the decision is supported by inspection data—not assumptions.

The goal is not to claim that problems cannot happen, but to avoid discovering them when there are no realistic options left.

Where Packaging Quality Control Usually Breaks Down — and How We Avoid It

Relying only on final inspection

Final inspection is often treated as the last line of defense for packaging quality.

In practice, it is only a confirmation step.

By the time packaging reaches final inspection, all critical decisions are already locked.

Materials are fixed. Processes are set. Quantities are committed.

If serious issues are discovered at this stage, the options are limited.

Sorting, rework, partial use, or restarting production are all expensive—and time-consuming.

We do not use final inspection to “find problems.”

We use it to confirm that shipped goods have no obvious defects.

At this point, the worst-case outcome should be re-inspection or controlled rescreening—

not discovering structural issues that require new materials or full re-production.

Approving samples without process alignment

Sample approval is often treated as the single signal to move into mass production.

In reality, it is rarely that simple.

A sample does not only represent the packaging itself.

It also affects downstream assembly, handling, and logistics—

steps that are often not visible during sampling but are critical in real use.

If packaging is difficult to assemble, slow to pack, or unstable during transport,

the frustration shows up later—when changes are hardest to make.

Saving a little on packaging often isn’t worth the trouble—

especially when assembly slows down or shipments arrive damaged at warehouses or stores.

We treat sample approval as a full-process checkpoint.

A sample is only approved when it reflects real assembly conditions,

real transport stress, and realistic handling—not just how it looks on the table.

Mismatch between packaging type and QC focus

Different packaging types fail in different ways.

Yet quality control is often applied using the same checklist.

Primary packaging allows almost no room for correction.

Secondary packaging depends heavily on visual and assembly consistency.

Tertiary packaging is tested by transport stress, not appearance.

Packaging is a perception-driven product.

Trying to check everything equally often means missing what actually matters.

We focus QC effort where failure would be felt most in real use,

rather than spreading attention evenly across low-risk details.

Why small pilot runs still deserve full attention

Pilot runs are often treated as the final trial before mass production.

Because volumes are small, the risks are often underestimated.

In reality, this stage carries the highest uncertainty.

Processes are new. Setups are still being adjusted. Assumptions are being tested.

If issues are ignored here, they rarely disappear.

They scale with volume—and become harder and more expensive to correct.

We apply the same QC discipline to pilot runs as to full production.

This is the stage where manual verification, machine testing,

and full-process checks are most effective.

When decisions are validated at the right time and at the right points,

mass production can move forward with confidence—and without surprises.

How Clients Can Tell QC Is Really Being Done

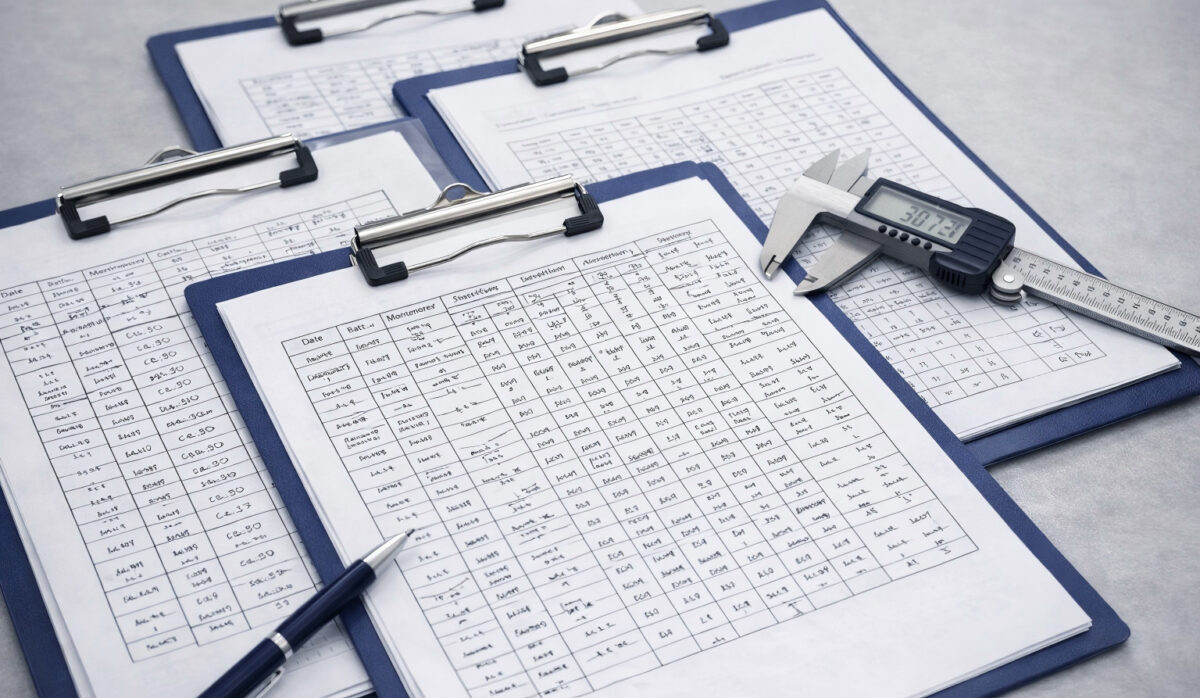

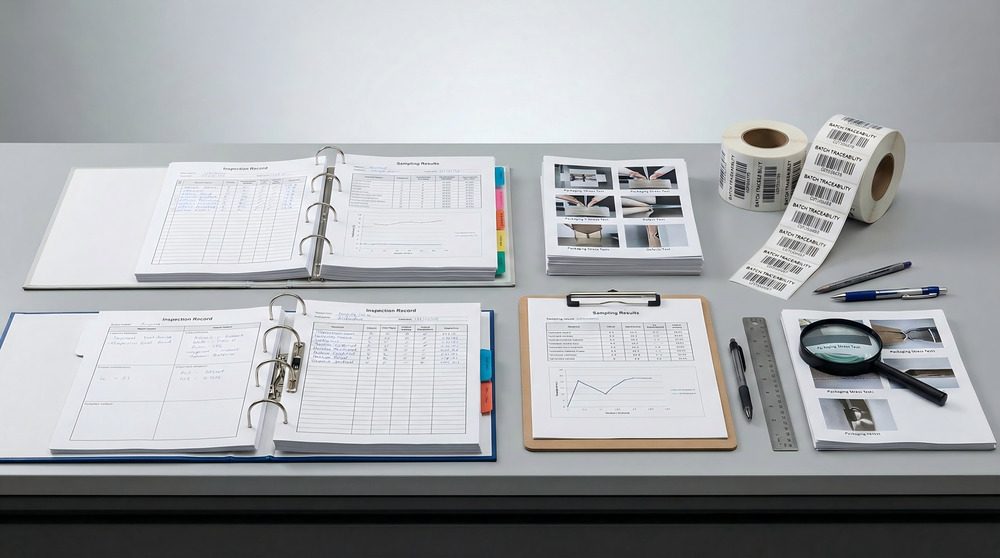

What meaningful QC records look like

Quality control is not defined by how many checks are claimed,

but by what can actually be reviewed.

Meaningful QC records are specific and traceable.

They show what was checked, when it was checked, and against which criteria.

Records that only say “passed” or “approved” offer little value.

Useful records show measurements, sampling results, and exceptions—

not just final conclusions.

When QC records can be reviewed after the fact,

they stop being paperwork and start becoming evidence.

What kind of transparency clients should expect

Transparency doesn’t mean sharing everything.

It means making the key points—and the key cautions—clear early.

Clients should be able to see how quality decisions are made,

especially when results sit near acceptance limits and require judgment.

This includes what was checked, the sampling logic used,

and what actions are taken when results are borderline.

If these points cannot be clearly explained,

issues are often discovered much later—when options are limited.

When transparency is built into the process,

quality discussions stay factual instead of emotional.

Questions we encourage clients to ask us

Strong QC doesn’t avoid questions.

It works better because of them.

We encourage clients to ask how quality is checked at each stage,

how borderline results are handled,

and how consistency is maintained across batches.

These are not theoretical questions.

They directly affect lead time, rework risk, and delivery stability.

When a client has special or non-standard requirements,

we treat them as controlled items

and build them into the QC plan for that specific job.

When both sides ask the right questions early,

many problems are resolved before production even begins.

QC evidence pack: what we can share (and what it proves)

Trust becomes real when it can be checked.

A QC evidence pack turns quality from a statement into something tangible.

It may include inspection records, sampling results, test photos or data,

and batch-level traceability information.

These materials are not meant to impress.

They exist to show how decisions were made and what was verified.

When QC evidence can be reviewed,

confidence comes from facts—not promises.

FAQ: Packaging Quality Control Questions We Hear Most Often

Is final inspection enough for packaging quality control?

No. Final inspection only confirms what is already finished.

By then, materials, processes, and quantities are fixed.

If a serious issue appears, the only options left are sorting, rework, or re-production.

Why do issues appear after sample approval?

Because a sample only proves something can be made once.

Production proves it can be repeated.

Only pilot runs or production-aligned samples—

using real processes, real QC steps, and transport tests—

can represent what will actually be delivered.

How strict should packaging quality control be?

As strict as the risk requires.

Start from what must not fail: protection, assembly, compliance, or brand appearance.

QC works when standards match real use—not just drawings.

Does packaging type affect QC requirements?

Yes. Different packaging fails in different ways.

Primary packaging allows little correction

Secondary packaging depends on consistency and assembly

Tertiary packaging must survive transport stress

Is QC different for small orders and mass production?

The goal is the same: reduce repeatable risk.

Small runs often need more attention, not less, because assumptions are still being tested.

Problems ignored at pilot stage usually grow after scale-up.

What QC records should clients ask to see?

Records that can be reviewed, not just conclusions.

Inspection results, sampling data, test photos or measurements, and batch traceability.

If decisions cannot be explained with records, QC is usually weak.

What does AQL sampling actually guarantee?

AQL shows whether a process is under control.

It does not promise zero defects.

We use AQL 1.0 to tighten risk control across stages,

but sampling never replaces stable processes.

Do you use 100% inspection for packaging?

Yes. Before packing, we normally perform 100% inspection.

Unless clients clearly accept minor appearance issues, every unit is screened.

Regardless of full inspection, AQL still runs from incoming materials to final audit to monitor process stability.

What “small” issues most often cause big losses?

Labels, barcodes, and markings.

They often look fine on the table, then fail in warehouses or stores.

When that happens, the real cost is delay, re-labeling, and disruption—not reprinting.

What tests matter most for transport packaging?

Tests that match real stress.

Drop, temperature cycling, and compression tests reveal weaknesses inspection alone cannot.

Packaging Quality Control Isn’t About Catching Mistakes —

It’s About Making Fewer Risky Decisions Together

Packaging quality control is not a safety net at the end of production.

It is a way to reduce risk by making the right decisions earlier.

Most packaging problems are not caused by missed inspections,

but by assumptions made too late—about materials, processes, or real use conditions.

When QC is treated as a shared decision system,

risks are addressed before they are produced,

and production becomes predictable instead of reactive.

That is what makes packaging reliable at scale

and partnerships sustainable over time.