Why Packaging Designs That Look Good Often Fail in Production?

A packaging design might look perfect in concept, but once it moves to production and shipping, unexpected challenges arise. Whether it’s weak structural integrity, unsuitable materials, or unexpected cost increases, many designs face problems after approval. This guide will walk you through how to avoid those pitfalls, ensuring your packaging is not only visually appealing but also manufacturable, cost-effective, and functional from the very beginning.

What Is Packaging Design? (Definition and Scope)

Packaging design is the process of designing a product’s structure, materials, and protection so it can be manufactured, shipped, and scaled reliably — not just how it looks.

That single sentence explains why so many packaging projects fail.

A box can look perfect on screen.

Colors approved. Layout approved. Brand team happy.

Then production starts.

Suddenly:

- The box doesn’t fold cleanly

- The product shifts inside

- Costs go up

- Damage appears during shipping

At that point, it’s already late.

Packaging design is not a visual task.

It’s a system decision that connects design, engineering, production, and logistics.

If any one part fails, the whole design fails.

Packaging Design vs Graphic Design

This is where confusion usually starts.

Graphic design is about communication.

It focuses on brand, layout, and visual hierarchy.

Packaging design goes further.

It also asks:

- How is this box built?

- What material can actually be used?

- Will it survive packing and shipping?

- Can it be produced consistently at scale?

A layout can look perfect on screen.

But if folds, glue areas, or tolerances don’t work in production, the design fails.

Good-looking packaging and workable packaging are not the same thing.

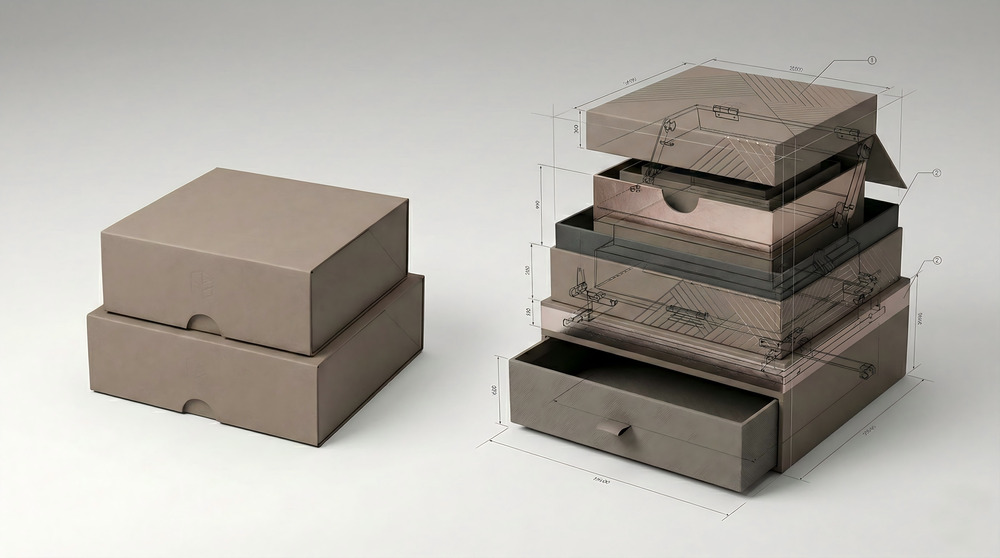

What Packaging Design Includes Beyond Visuals

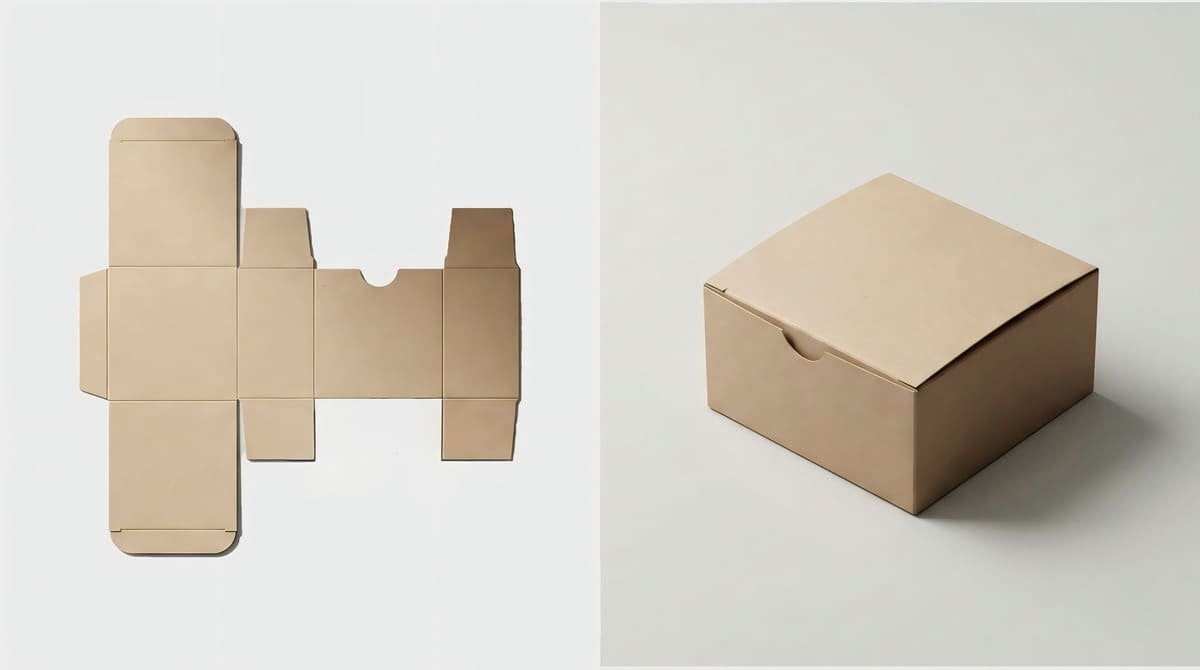

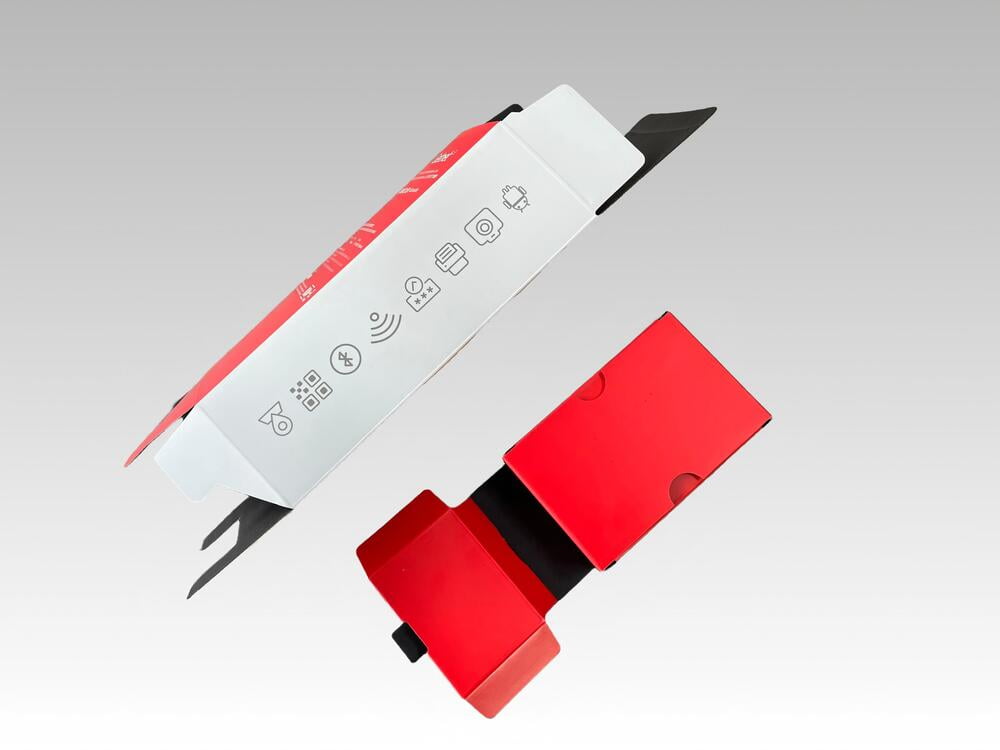

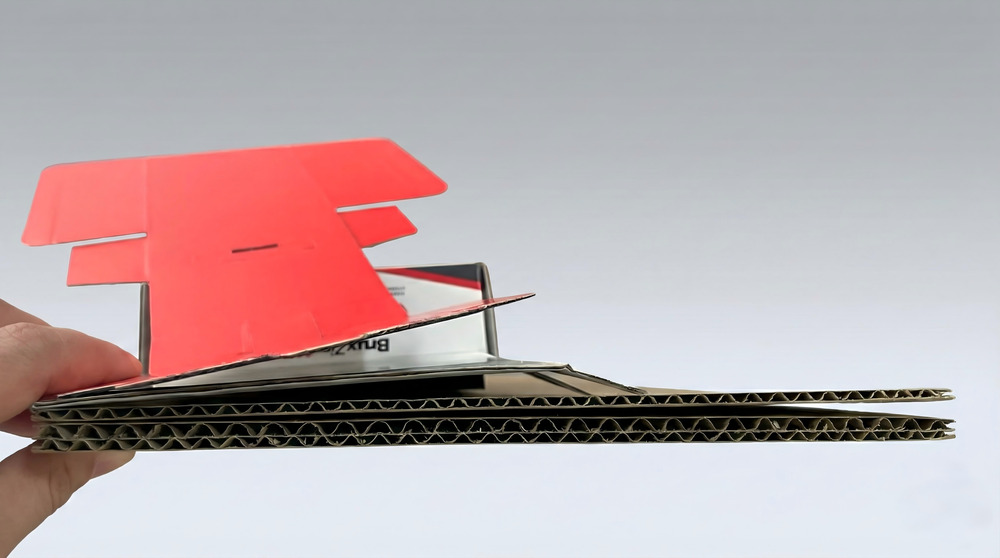

A real production example showing how outer box structure and inner inserts work together beyond visual design.

Structure

Structure defines how the packaging holds the product.

It includes:

- Box style and opening method

- Internal supports or inserts

- Folding lines and glue areas

Structural decisions affect strength, assembly speed, and unit cost.

They are also difficult to change later.

Materials

Material choice is not just about thickness or feel.

It affects:

- Durability

- Print quality

- Color consistency

- Compatibility with coatings and finishes

A thicker board does not automatically mean stronger packaging.

Protection

Protection is about what happens after the box leaves the factory.

It must account for:

- Drops and impacts

- Compression during stacking

- Long-distance transport

- Temperature and humidity changes

If protection is treated as an afterthought, damage usually shows up later.

Manufacturability

Manufacturability determines whether a design can be produced consistently.

It includes:

- Machine limitations

- Folding accuracy

- Glue strength and placement

- Tolerance control

Many failures come from designs that ignore how factories actually work.

Shipping considerations

Shipping changes everything.

Designs must account for:

- Carton packing methods

- Pallet stacking

- Container loading

- Long transit times

Packaging that survives local handling can still fail in international shipping.

Quick insight:

If you’re unsure whether these decisions will hold up in production, pause here.

We’ve summarized the key checks we use in real projects into a practical packaging design guideline:

👉 Download the Packaging Design Guideline (PDF)

The Packaging Design Process: Step-by-Step

Packaging design is not just about creating a box. It’s a decision-making process that affects cost, logistics, risk, and long-term scalability. Below is a practical, step-by-step approach used in real packaging projects, from concept to mass production.

Step 1: Understand the Product and Use Case

Every packaging decision starts with the product itself. Before structures or materials are discussed, the basics must be clear:

- Product size and weight

- Fragility and protection requirements

- Sales channels (e-commerce, retail, or both)

- Market positioning and price point

Once these are defined, the packaging can be evaluated against what it actually needs to achieve—not what looks good on screen.

Step 2: Choose the Right Packaging Structure

The structure determines how the packaging performs across protection, cost, logistics, and presentation. Common options include:

- Rigid Boxes: Traditionally used for premium products, offering strong protection and a high-end appearance.

- Folding Cartons: Lightweight, efficient, and widely used for retail packaging.

- Corrugated Boxes: Durable and cost-effective, suitable for shipping and combined retail-plus-logistics use.

In today’s competitive environment, corrugated color boxes are increasingly the most widely used structure, positioned between rigid boxes and folding cartons in both cost and performance.

At the same time, rigid boxes are shifting toward foldable, flat-pack rigid structures, which significantly reduce logistics and storage costs compared to traditional fixed rigid boxes.

Step 3: Select Materials Based on Performance, Not Assumptions

Material choices should be driven by performance requirements, not habits or assumptions. In practice, the most common options include:

Paperboard: Used for folding cartons and rigid boxes. FSC-certified paperboard is commonly chosen when print quality and sustainability both matter.

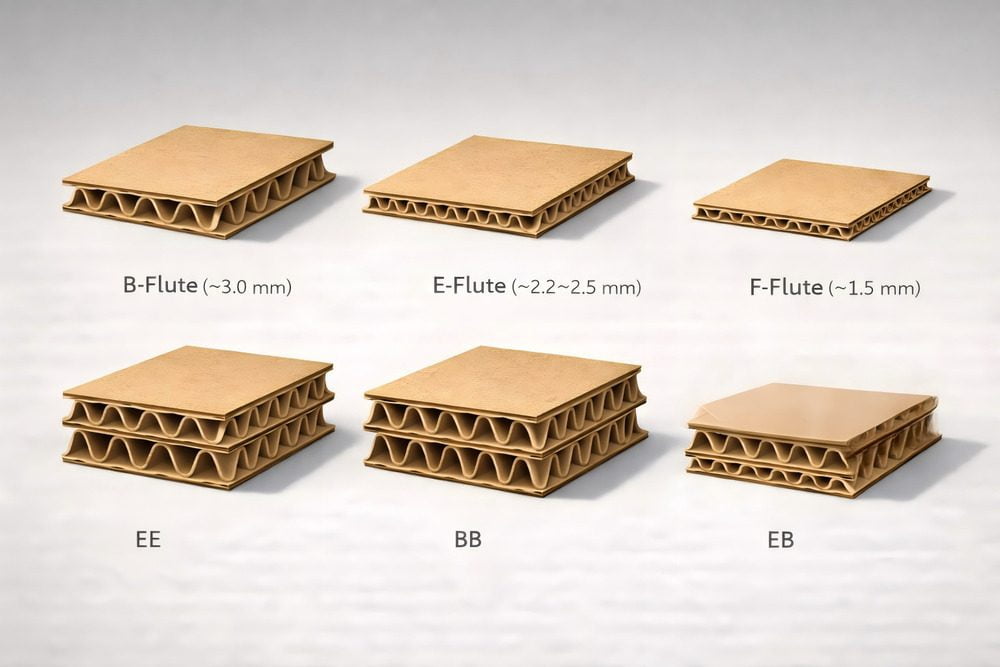

Corrugated Board: Commonly used for shipping and protective packaging. Typical single-wall flute options include:

- B-flute (≈ 3.0 mm): Suitable for heavier products and stronger stacking requirements.

- E-flute (≈ 2.2–2.5 mm): A balance between strength and print quality, often used for retail-ready packaging.

- F-flute (≈ 1.5 mm): Thin and refined, suitable for lightweight products and compact designs.

When higher rigidity is needed, double-wall combinations such as EE-flute, BB-flute, or EB-flute can be used depending on compression and protection requirements.

- Molded Pulp & Paper Inserts: Paper-based alternatives used for product positioning and protection.

A simple way to decide between paperboard inserts and molded pulp inserts:

- Small quantities or urgent timelines → folded paper inserts

- Large volumes with stable, long-term demand and precise fit requirements → molded pulp inserts

Step 4: Design for Manufacturability (DFM)

Design for Manufacturability ensures that a packaging concept can actually be produced at scale. Key considerations include:

- Die-cut layouts that match standard production capabilities

- Realistic glue areas suitable for automated assembly

- Proper tolerances to account for material and process variation

DFM must be considered at the very beginning of the design process. If manufacturability issues are discovered later, fixing them often means redesigning structures, remaking tooling, and delaying production—costly problems that are far harder to correct once decisions are locked in.

Step 5: Prototyping, Sampling, and Testing

A great design on a computer screen is just the start. In the real world, a box needs to stay strong and functional. We create physical samples to check three key areas:

- Fit and Sizing: Does the product fit perfectly inside without moving?

- Structural Strength: Can the edges and folds handle pressure without tearing?

- Secure Closure: Do the lids, flaps, and magnets stay closed during handling?

For export projects, we also integrate our packaging quality control protocols at this stage. This allows us to test the design against shipping stress before we commit to mass production.

Step 6: Final Design Approval Before Mass Production

Before production begins, all decisions must be locked:

- Cost confirmation based on final structure and materials

- Quality standards for printing, structure, and assembly

- Compliance checks for barcodes, certifications, and required information

From experience, it is strongly recommended to share your packaging budget at the very beginning of the design stage. With a clear budget range, multiple structure and material options can be evaluated upfront—along with their costs and trade-offs—avoiding the need to overturn earlier decisions later, which is frustrating, time-consuming, and completely avoidable.

Types of Packaging Structures and When to Use Them

Packaging structure is a decision about function first, not decoration.

Before materials, finishes, or printing methods are discussed, the structure defines how the packaging performs—during packing, shipping, storage, and final presentation.

In real packaging projects, most downstream issues originate from choosing a structure that does not match the product’s weight, size, or distribution model.

This section compares the most commonly used paper-based packaging structures and explains when each structure makes sense, based on practical manufacturing and logistics considerations.

Rigid Boxes

Rigid boxes are built with thick paperboard—most commonly grey board—and wrapped with printed or specialty paper.

What defines a rigid box is structural stiffness once assembled, not whether it ships flat or pre-assembled.

In practice, rigid boxes usually appear in two forms:

- Pre-assembled rigid boxes, delivered fully set-up

- Foldable or collapsible rigid boxes, assembled during packing

Both belong to the rigid box category because the load-bearing structure comes from solid board rather than folding paperboard.

With the advancement of automated production and assembly equipment, foldable rigid boxes and collapsible rigid gift boxes have become increasingly popular. They retain the premium look and stiffness of traditional rigid boxes, while offering shipping and storage efficiency that approaches corrugated cartons in terms of volume.

In practice, the decision is rarely about whether a box can fold.

It is about whether the product requires rigid structural support after assembly. From a cost perspective, smaller-sized products often favor pre-assembled set-up rigid boxes, while larger formats benefit more from collapsible rigid gift boxes that ship flat.

Folding Cartons

Folding cartons are made from single-sheet or double-laminated paperboard that is die-cut and normally delivered flat.

Depending on size and application, some small-format folding cartons designed for lightweight products may also be delivered pre-formed.

Structurally, folding cartons are chosen for flexibility and efficiency. They can be folded into a wide range of shapes and are well suited for automated packing lines and scalable production.

Folding cartons are commonly used when:

- The product is relatively lightweight and easy to support structurally

- The packaging needs to adapt to different shapes or SKUs

- Cost control and print efficiency are key considerations

For heavier products, folding cartons are often combined with engineered paper inserts, allowing the outer carton to remain lightweight while the internal structure handles load-bearing and protection.

Corrugated Boxes

Corrugated boxes are made from fluted paperboard sandwiched between linerboards.

Their primary role is strength, cushioning, and transport stability, rather than presentation.

Corrugated packaging is typically selected when:

- Products need protection during shipping and stacking

- Distribution involves long-distance transport or e-commerce fulfillment

- The packaging must perform reliably across varying logistics environments

From a cost perspective, corrugated boxes generally sit between rigid boxes and folding cartons. Except for very small-format cartons, corrugated packaging is the most widely used structure because it balances protection, cost efficiency, and scalability.

Hybrid Packaging Structures

Hybrid packaging structures combine multiple paper-based structures within a single packaging system—for example, a rigid or folding carton paired with a corrugated outer box, or a folding carton combined with molded paper inserts.

Hybrid structures are usually chosen when:

- No single structure can meet all functional requirements

- Presentation and logistics place competing demands on the packaging

- The product moves through multiple channels before reaching the end user

Rather than upgrading materials blindly, hybrid packaging assigns each component a clear role—presentation, protection, or transport efficiency—within the overall system.

Packaging Materials Explained

When discussing packaging materials, most confusion does not come from a lack of options, but from misunderstanding how materials actually behave once they are converted into real packaging.

In practice, material decisions only make sense when evaluated together with structure, print method, and production conditions. This section explains common paper-based packaging materials from a practical manufacturing perspective, focusing on how they are typically used and what they are realistically suited for.

Common Paperboard Materials

Most paper-based packaging relies on a relatively small group of core materials, especially for paper boxes and folded inserts.

The difference between packaging projects usually comes from how these materials are applied, rather than from discovering new paper types.

In everyday packaging production, the most commonly used paperboard materials include:

- Solid Bleached Sulfate (SBS), often chosen for clean print results and high-end paper packaging

- Coated Recycled Board (CRB / CCNB), commonly used for cost-sensitive paper packaging

- Grey board (normally grey-back, white-back, or black-back), primarily used in rigid boxes where structural stiffness is required

- Corrugated board, laminated with outer paper, used when stacking strength and transport protection are priorities

- Kraft paper (natural brown or white options), often selected for non-laminated finishes or skin-texture surfaces to express a more natural packaging feel

A common misunderstanding is to treat material choice as a standalone decision.

In practice, materials only make sense in relation to the structure they support. A board that performs well in a folding carton may be unsuitable for a rigid box, while a structurally strong board may be unnecessary for a print-driven retail carton.

The key question is not “Which paper is better?”

It is “What role does this material play in the finished package?”

Thickness vs Strength: Common Myths

Thickness is often treated as a shortcut for strength, but in paper-based packaging, thickness alone is not a reliable indicator of performance.

In practice, strength comes from a combination of factors, including:

- How well the packaging strength matches the actual product weight and usage

- How layers are laminated or fluted

- How the material works within the chosen structure

A thicker sheet does not automatically result in a stronger package.

In real-world packaging, “suitable” matters more than “thicker”.

For folding cartons and corrugated paper boxes, excessive thickness can reduce folding accuracy, slow down packing, and increase unnecessary costs.

For rigid boxes, insufficient board density can lead to deformation even when the thickness appears adequate.

At Klong Packaging, experienced packaging decisions evaluate thickness together with structure, rather than blindly following client habits or defaulting to stronger and thicker materials. Choosing the right material is not about overengineering—it is about balancing performance and cost.

Print Quality vs Design Trade-offs

We often receive design files from designers that look beautiful and highly refined on screen. However, during actual mass production, several practical issues are frequently overlooked.

Common examples include:

- Fine foil stamping lines, especially gold or silver, may merge during mass production. Two very thin lines in a design can easily become one line after stamping.

- Kraft paper, due to its higher absorbency, makes precise registration difficult. When designs rely on accurate alignment for spot UV, gold foil, or silver foil, visible misalignment is very common in production.

- Dark color packaging, where the background color and text or patterns differ by only around 5% in tone or Pantone value, may look clear on screen. In reality, these elements often blend together, making text and graphics difficult to recognize at first glance.

A good packaging partner does not simply produce what is provided.

From design files to structure and production conditions, standing on the same side as the brand to make packaging work in reality is something Klong Packaging has consistently focused on.

In practice, print quality and design effect should be evaluated together with production feasibility. The goal is not to reduce creativity, but to ensure that design intent survives real manufacturing conditions and large-scale production.

Sustainable Packaging: What Works in Reality

Sustainable packaging decisions work best when they are based on how materials perform in real packaging systems, not on labels alone.

Raw materials, surface treatments, and processing methods all influence sustainability outcomes—but only when they align with functional requirements and actual production quantities. A material that fits the structure well, performs consistently, and is suitable for mass production often leads to more sustainable results than a material chosen purely for perception.

In practice, sustainable packaging works when:

- The material matches the structural role without overengineering

- Surface treatments are used deliberately

- Durability is aligned with the product’s lifecycle

Sustainability, in this context, is not a single material choice.

It is the result of material, structure, and usage working together efficiently.

Design for Manufacturability (DFM): Why Packaging Designs Fail

Many packaging designs fail not because they look bad, but because they are designed in isolation from how they will actually be produced.

In packaging, a design only succeeds if it can be manufactured repeatedly, assembled efficiently, and controlled at scale. When design decisions ignore production reality, problems rarely appear on screen—they surface during sampling, trial runs, or mass production.

Design for Manufacturability (DFM) in packaging is not about restricting creativity.

It is about preventing avoidable failure by aligning design intent with material behavior, machine capability, and production tolerance from the beginning.

What Is DFM in Packaging Design?

In packaging, DFM means designing structures, graphics, and finishes with manufacturing reality built into the design stage, not corrected afterward.

A DFM-ready packaging design considers questions such as:

- Can this structure be folded and glued consistently at production speed?

- Are glue areas realistic for the selected material and surface treatment?

- Will small dimensional deviations affect fit, assembly, or visual alignment?

Unlike product design, packaging relies heavily on high-speed, semi-automated, or fully automated processes. This makes packaging designs extremely sensitive to details that may seem minor in design software but become critical during mass production.

In practice, DFM is less about adding rules and more about removing assumptions—especially the assumption that materials, machines, and people behave as precisely as CAD files.

Common DFM Issues in Packaging

Most DFM failures in packaging are not caused by complex engineering problems.

They come from a small number of recurring issues that are often underestimated during design.

These are not the only DFM issues that exist, but they are the most common and the most damaging when ignored.

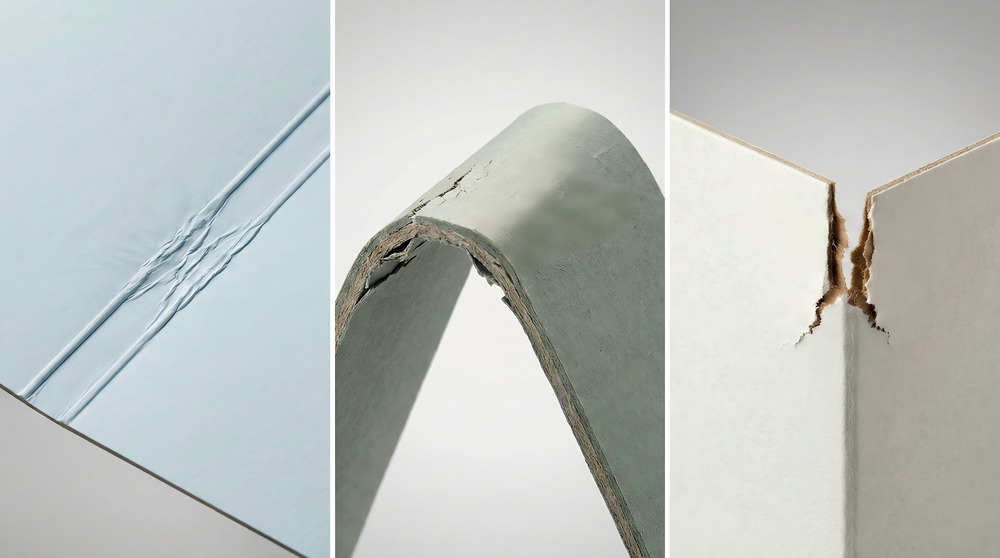

Folding limitations

Not every fold that looks clean in a dieline will behave well on the production floor.

Common problems appear when:

- Fold lines are placed too close to each other

- Board thickness is ignored in multi-layer or reverse folds

- Sharp angles are pushed beyond what the material can tolerate

In real production, folding accuracy depends on material stiffness, fiber direction, die-cut accuracy, and machine setup. When folding behavior is not considered early, boxes may crack, fail to stay closed, or show inconsistent shapes across batches.

Glue areas

Glue is often treated as a secondary detail in design, but in production it is one of the most frequent failure points.

Typical issues include:

- Glue areas that are too small for stable bonding

- Glue zones placed on coated or laminated surfaces without adjustment

- Designs that assume manual precision on automated or semi-automated lines

In practice, glue requires space, tolerance, and compatibility with both the material and the surface finish. When this is ignored, the result is weak bonding, visible glue marks, or unstable box assembly during packing.

Tolerances

Perfect alignment exists in design software—not in mass production.

In real packaging production, dimensional deviation after forming typically falls within 50%–100% of the material thickness, and this range is considered normal. For this reason, inserts and outer boxes must never be designed for zero-gap fitting. Clearance must be intentionally built into the structure.

In addition, during the die-cutting process, printed artwork requires buffer zones.

As a general production rule, a minimum of 3 mm bleed on all four sides is necessary to prevent white edges from appearing due to cutting deviation.

When tolerance is not built into the design, small deviations accumulate quickly—leading to poor fit, misalignment, and inconsistent appearance across production batches.

When to Involve a Manufacturer or Engineer

One of the most common packaging mistakes is involving manufacturing input too late.

In practice, a manufacturer or packaging engineer should be involved when:

- Structural complexity goes beyond standard box styles

- Multiple materials or surface finishes are combined

- Tight visual alignment or precise assembly is required

- A startup lacks an in-house professional packaging designer

- A brand is developing packaging for a new product line from scratch

Early involvement does not slow down design.

It reduces rework, prevents repeated sampling, and avoids structural decisions that cannot be corrected cheaply once tooling or mass production begins.

DFM works best when design and manufacturing are treated as one continuous process, not two separate stages handed off at the last minute.

Cost, MOQ, and Lead Time Considerations in Packaging Design

In packaging, cost, minimum order quantity, and lead time are not variables to be negotiated later.

They are direct consequences of design decisions—often locked in long before pricing discussions begin.

Packaging design defines how many steps are required, how stable production can be, and how easily a project can scale. This section focuses on which design choices drive commercial outcomes, and where teams most commonly underestimate their impact.

How Packaging Design Affects Unit Cost

Unit cost is rarely driven by material price alone.

In real production, cost increases when a design slows down repetition.

Design choices that most commonly push unit cost higher include:

- Overly complex structures that require manual intervention

- Multi-layer constructions that increase handling and alignment time

- Decorative finishes that add extra setup or secondary processes

A design may look minimal, but if it disrupts folding speed, gluing stability, or quality consistency, cost rises quickly.

Well-designed packaging controls cost by reducing variation, not by reducing visual quality.

For startups, higher unit cost is often tolerated during early validation.

For scale-up brands, the same design quickly becomes unsustainable when volume increases.

Why Some Designs Require Higher MOQs

MOQs increase when designs require resources that cannot be shared or easily amortized.

The most common design-driven reasons for higher MOQs include:

- Special customized raw materials or tooling, such as specialty-colored or textured paper, custom-colored foil, non-standard molded pulp inserts (for example, white pulp trays that differ from commonly used off-white stock), or insert designs where order volume is insufficient to amortize mold costs

- Structural designs that require long machine setup and calibration time, making short production runs inefficient

- Tolerance requirements beyond standard paper packaging limits, such as cylindrical paper tube boxes where full-surface graphics must align after assembly within ±0.5 mm

For early-stage brands, these factors often result in higher upfront commitments and reduced flexibility.

For scale-up brands, they usually signal that the design is not optimized for stable, repeatable production.

In practice, MOQs are not a pricing strategy.

They are a reflection of how efficiently a design can enter and remain in mass production.

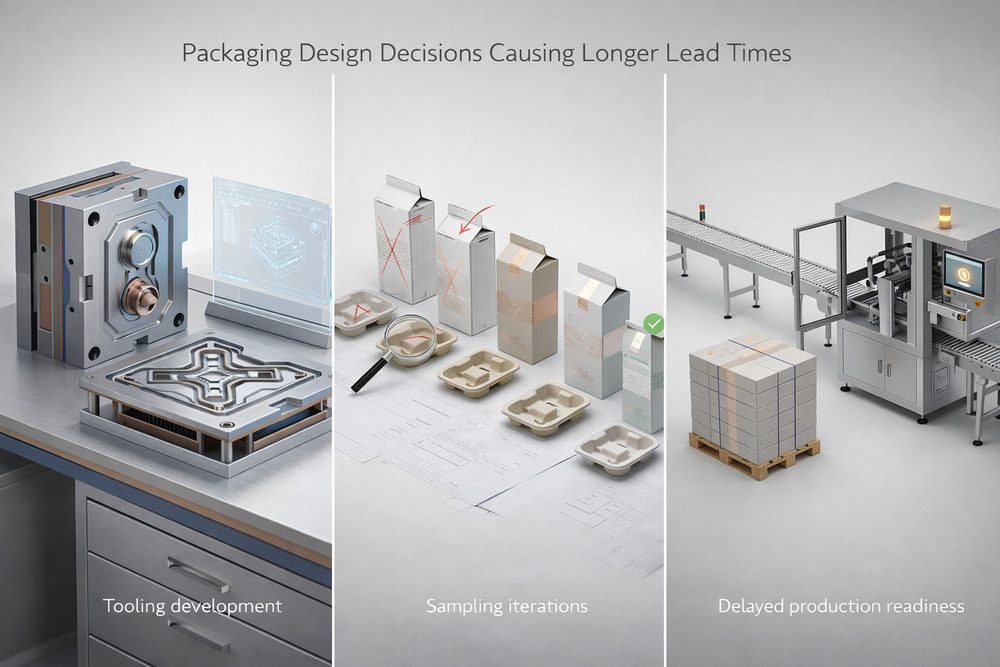

Design Choices That Increase Lead Time

Lead time extends when design decisions delay production readiness.

Design elements that consistently increase lead time include:

- Structures that require multiple rounds of sampling

- Tooling that cannot be finalized due to late-stage design changes

- Materials or finishes with longer sourcing or preparation cycles

Long lead times are rarely caused by slow manufacturing.

They are caused by designs that are still being adjusted when production should already be running.

For startups, longer lead times delay market entry.

For scale-up brands, they disrupt launch schedules and inventory planning.

What Design Decisions Are Hard to Change Later

Not all design decisions carry the same cost of change.

Design choices that are difficult and expensive to reverse include:

- Structural formats tied to tooling or molds

- Dimensions that affect inserts, shipping efficiency, or palletization

- Material selections that limit finishing options or sourcing flexibility

These decisions lock in cost, MOQ, and lead time early.

Later changes often require new tooling, new samples, and extended timelines.

By contrast, surface-level adjustments—such as minor graphics or color tweaks—remain relatively flexible.

Understanding this distinction helps teams focus their effort where design decisions truly matter.

Packaging Testing and Shipping Risks

Why Visual Approval Is Not Enough

Visual approval confirms appearance, not shipping performance.

Visual approval evaluates how packaging looks—structure, print, color, and finishing.

However, shipping stress comes from forces that are not visible: impact, compression, vibration, temperature change, and humidity.

Common shipping failures that visual checks cannot reveal include:

- Box deformation after extended stacking

- Internal movement caused by repeated vibration

- Surface scuffing or adhesion under heat and pressure

In practice, most failures occur after repeated handling, not during the first incident.

Testing verifies how packaging behaves across the full logistics cycle—not just how it looks at rest.

Packaging that performs well in local handling can still fail—or become inefficient—once it enters international shipping.

Shipping risk is not only about damage. It is also about efficiency and repeatability at scale.

In practice, packaging design should account not only for product protection, but also for how finished pack dimensions interact with standard container loading. By referencing standard container internal dimensions early in the structural design phase, packaging sizes can be planned to improve container utilization instead of being adjusted later as a logistics fix.

This does not change how the product is protected. It changes how efficiently space is used during transport—and directly affects total landed cost.

Common Packaging Tests

Packaging tests simulate real shipping stress, not ideal conditions.

They are used to identify weaknesses before products reach customers.

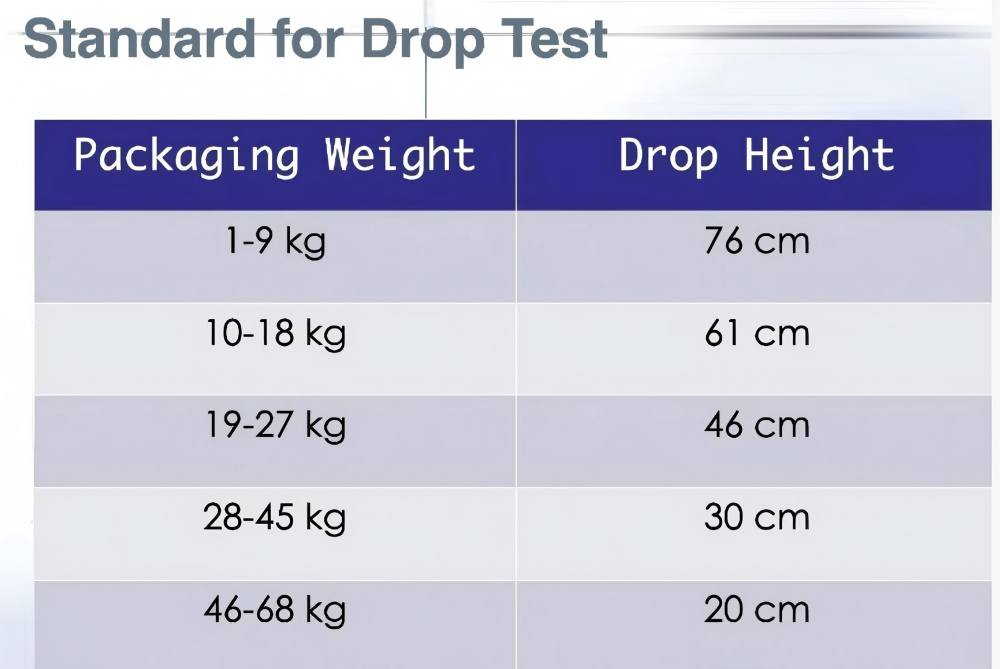

Drop tests

What drop tests evaluate

Drop tests simulate impacts during manual handling, loading, unloading, and sorting.

Common international reference values by gross weight include:

- 1–9 kg: 76 cm

- 10–18 kg: 61 cm

- 19–27 kg: 46 cm

- 28–45 kg: 30 cm

- 46–68 kg: 20 cm

Standard validation method

- One corner

- Three edges

- Six faces

- Total: 10 drops

Two-stage testing for sensitive or electronic products

- Single-pack testing at a fixed height of 1 meter to evaluate primary packaging performance

- Outer carton testing, where multiple units are packed and tested again based on total weight

This staged approach helps identify internal protection issues before scaling to full-carton testing.

Compression tests

What compression tests evaluate

Compression testing evaluates how corrugated board and assembled cartons perform under vertical load.

Two commonly confused tests

- Burst test: measures how much force is required to rupture flat corrugated board

- Compression test: measures vertical stacking strength and carton deformation resistance

Compression testing is used to verify:

- Corrugated flute stiffness when standing vertically

- Carton performance during pallet stacking

- Whether lower layers deform under sustained load

Many shipping failures occur without visible impact, making compression testing critical for warehousing and container transport.

Temperature and humidity tests

What environmental tests validate

Temperature and humidity testing evaluates packaging performance under environmental stress.

Typical test conditions

- Temperature range: –20°C to 60°C

- Humidity: up to 85% RH

- Duration: 48–72 hours (cyclic testing)

These tests verify:

- Adhesive integrity after exposure, with normal forming and light tearing showing no glue failure

- Bond strength between liner paper and corrugated medium or paperboard

- Optional validation: immediate tearing after testing to confirm fiber failure rather than adhesive failure

Environmental testing confirms packaging stability across realistic shipping and storage conditions.

When Testing Is Necessary (And When It’s Not)

Testing should be applied selectively, not universally.

Testing is usually necessary when:

- Products are fragile, sensitive, or high-value

- Packaging structures are new or unproven

- Shipping involves long distances, cross-climate transport, or multiple handling stages

Testing may be unnecessary when:

- Structures and materials are already proven

- Distribution conditions are controlled and predictable

- Packaging is used mainly for short-distance or internal logistics

In practice, testing delivers value when the cost of failure exceeds the cost of validation.

Common Packaging Design Mistakes to Avoid

Many packaging problems do not come from lack of creativity.

They come from decisions that seem reasonable early on, but create friction once production, packing, and shipping begin.

These mistakes are common across industries and company sizes.

Avoiding them does not require more complex design—it requires clearer priorities and earlier consideration of how packaging is actually used.

Designing for Appearance Only

Packaging that looks impressive on screen or in mockups can fail quickly in real use.

Designs focused solely on appearance often ignore:

- How materials behave when folded, glued, or stacked

- How finishes perform under friction, pressure, or humidity

- How small visual details survive mass production tolerance

In practice, appearance-only design leads to packaging that photographs well but performs inconsistently.

Good packaging design balances visual impact with structural and production reality from the start.

Ignoring Packing and Assembly

Packaging is rarely used in isolation.

It must be packed, assembled, and handled—often at speed.

Common issues arise when designs do not consider:

- How easily products can be inserted

- Whether assembly steps are intuitive and repeatable

- How packaging behaves on real packing lines

A design that requires extra handling, manual adjustment, or careful alignment increases labor cost and error rates.

Ignoring packing and assembly turns small design inefficiencies into ongoing operational problems.

Over-Engineering Early Designs

Over-engineering is often mistaken for quality.

Early-stage designs frequently become too complex because:

- Designers try to solve future problems prematurely

- Structures are reinforced beyond actual requirements

- Materials are selected based on “maximum performance” rather than real use

- Special materials or production processes are added even when they create little noticeable value for the end consumer

This approach increases cost, MOQ, and lead time before real validation occurs.

In practice, early designs benefit more from controlled simplicity—allowing performance to be proven first—rather than committing early to excessive reinforcement or hard-to-perceive upgrades.

Skipping Validation Before Production

Validation is often delayed in the interest of speed or budget.

When validation is skipped, problems tend to appear:

- During initial production runs

- After packaging enters shipping or storage

- Once issues reach customers

Visual approval alone cannot reveal performance under impact, stacking, or environmental stress.

Skipping validation does not save time—it shifts risk to a later and more expensive stage.

Assuming Sustainable Packaging Always Costs More

Sustainability is often treated as a premium feature rather than a system decision.

This assumption leads to:

- Over-specifying materials or finishes

- Adding sustainability elements without functional alignment

- Missing opportunities to reduce material usage through better structure

In practice, sustainable packaging often comes from using the right material in the right structure, not from using more expensive materials.

Cost increases usually result from misalignment—not from sustainability itself.

Packaging Design FAQ

What makes good packaging design?

Good packaging design works reliably in production, packing, and shipping—not just in visuals.

Good packaging design balances four things:

Function: the structure protects the product in its real use scenario

Manufacturability: folding, gluing, and tolerances are realistic at scale

Efficiency: packing and assembly can be repeated without extra labor or errors

Brand impact: customers can actually perceive the intended quality

If a design looks good but cannot be produced or packed consistently, it is not finished.

How much does packaging design affect cost?

Packaging design affects cost mainly by changing how efficiently it can be repeated at scale.

Cost is rarely driven by material price alone.

Design choices influence:

how many processes are required

how stable production is after setup

how efficient packing and assembly can be

A visually simple design can still be expensive if it slows production or increases error rates.

In mass production, cost is the cost of repetition—not the cost of one sample.

Do I need a manufacturer involved during design?

Early manufacturer involvement reduces assumptions, revisions, and delays.

A manufacturer or packaging engineer should be involved early when:

the structure is new or complex

multiple materials or finishes are combined

tight alignment or precision is required

a startup lacks an in-house packaging specialist

a new product line is being developed

The goal is not to replace design decisions, but to confirm feasibility before costs are locked in.

Do all products require packaging testing?

No—testing is a risk-based decision, not a mandatory step.

Testing is usually necessary when:

products are fragile, sensitive, or high-value

shipping involves long distance, multiple handling stages, or climate changes

the structure or material combination is new

Testing may be unnecessary when:

proven structures and materials are reused

distribution conditions are predictable

packaging is for short-distance or internal logistics

Testing makes sense when the cost of failure is higher than the cost of validation.

Can packaging design problems be fixed after production starts?

Some issues can be adjusted, but core design decisions are hard to reverse once production begins.

Difficult-to-change decisions include:

structures tied to tooling or molds

dimensions affecting inserts, shipping, or palletization

material choices that limit finishing or sourcing

Minor artwork or surface-level adjustments are usually flexible.

Structural and dimensional changes rarely are.

What information is needed to start packaging development?

Packaging development starts with understanding the full contents—not just the main product.

To proceed efficiently, a packaging manufacturer typically needs:

the product and all accessories included in the package

if physical samples are unavailable, 3D files of the product and accessories for structural development

basic usage and shipping context (retail, e-commerce, or both)

Without a clear definition of what goes inside the package, structural decisions become assumptions.

What’s the most efficient sampling process for new products?

The fastest sampling process separates structure validation from final printing decisions.

For new products, a cost- and time-efficient workflow usually follows this order:

Confirm packaging requirements and constraints

Develop and review blank structural samples

Place artwork on the finalized dieline

If artwork is confirmed, proceed to formal samples or pilot production

If artwork is not confirmed, review free digital mockup samples first

Locking material, size, and structure before formal samples is the safest way to avoid rework, reduce cost, and shorten timelines.

Why do tight alignment requirements increase cost and risk?

Tight alignment increases risk because packaging is formed material, not a rigid object.

Paper-based packaging naturally includes forming and tolerance variation.

When alignment requirements are extremely tight—such as full-wrap graphics on cylindrical or folded structures—production risk increases.

In practice, experienced packaging manufacturers will:

communicate feasibility and tolerance limits before sampling

adjust artwork files to reduce sensitivity

provide revised files or digital samples for confirmation

Early feasibility checks help prevent costly re-sampling or re-tooling later.

How do I choose between rigid boxes, folding cartons, and corrugated boxes?

The right structure depends on what must be true at the end of use.

A simple decision logic:

Rigid boxes: when premium feel and stiffness are part of the product experience

Folding cartons: when retail presentation and production efficiency are both needed

Corrugated boxes: when protection, shipping efficiency, and stacking strength matter most

When unsure, decide based on the primary goal: shelf impact, packing speed, shipping survival, or total landed cost.

Does sustainable packaging always cost more?

Sustainability increases cost only when it is treated as a feature instead of a system.

Sustainable results often come from:

choosing the right structure to reduce material

avoiding unnecessary layers or finishes

selecting materials that perform consistently in mass production

In many cases, better structural design lowers both environmental impact and cost.

How can I switch to 100% plastic-free materials without losing a luxury feel?

Stop trying to make paper act like plastic. In 2026, luxury is defined by Tactile Precision. We suggest replacing plastic-based soft-touch films with high-density, Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified papers. Use deep blind embossing or micro-textures to create a high-end sensory experience that is 100% recyclable. This ensures your brand meets environmental laws while maintaining a premium, “expensive” feel.

What is the most realistic way to lower costs while meeting new 2026 environmental taxes?

The secret is Mono-Material Engineering (designing a package from a single type of fiber). This makes the entire package 100% curbside recyclable. This strategy protects your brand from rising Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) fees—environmental taxes now increasing across Europe and the U.S. By removing plastic windows and complex laminates, you simplify the supply chain and significantly reduce the total cost of ownership.

Can AI design software replace the need for professional structural packaging engineers?

AI is a fast Brush, but it is not an Architect. While AI can generate thousands of visual mockups, it does not understand Design for Manufacturing (DfM) logic. A design might look perfect on a screen, but if the structural geometry ignores paper grain or machine glue pressure, it will fail on the production line. You need a structural expert to ensure that AI-generated concepts can actually be produced at scale with zero defects.

Packaging design is more than design files.

It is complete only when those files can be produced, assembled, and shipped without repeated correction.

In practice, reliable packaging design follows a simple order:

review the structure, check manufacturability, and validate early with samples.

These steps are not extra work.

They are what prevent packaging from becoming expensive to fix later.

When structure, manufacturability, and validation are considered early, packaging stops being a design risk—and becomes a controllable system.